Encyclopedia for Writers

Composing with ai, using first person in an academic essay: when is it okay.

- CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 by Jenna Pack Sheffield

Related Concepts: Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community ; First-Person Point of View ; Rhetorical Analysis; Rhetorical Stance ; The First Person ; Voice

In order to determine whether or not you can speak or write from the first-person point of view, you need to engage in rhetorical analysis. You need to question whether your audience values and accepts the first person as a legitimate rhetorical stance. Source:Many times, high school students are told not to use first person (“I,” “we,” “my,” “us,” and so forth) in their essays. As a college student, you should realize that this is a rule that can and should be broken—at the right time, of course.

By now, you’ve probably written a personal essay, memoir, or narrative that used first person. After all, how could you write a personal essay about yourself, for instance, without using the dreaded “I” word?

However, academic essays differ from personal essays; they are typically researched and use a formal tone . Because of these differences, when students write an academic essay, they quickly shy away from first person because of what they have been told in high school or because they believe that first person feels too informal for an intellectual, researched text. While first person can definitely be overused in academic essays (which is likely why your teachers tell you not to use it), there are moments in a paper when it is not only appropriate, but also more effective and/or persuasive to use first person. The following are a few instances in which it is appropriate to use first person in an academic essay:

- Including a personal anecdote: You have more than likely been told that you need a strong “hook” to draw your readers in during an introduction. Sometimes, the best hook is a personal anecdote, or a short amusing story about yourself. In this situation, it would seem unnatural not to use first-person pronouns such as “I” and “myself.” Your readers will appreciate the personal touch and will want to keep reading! (For more information about incorporating personal anecdotes into your writing, see “ Employing Narrative in an Essay .”)

- Establishing your credibility ( ethos ): Ethos is a term stemming back to Ancient Greece that essentially means “character” in the sense of trustworthiness or credibility. A writer can establish her ethos by convincing the reader that she is trustworthy source. Oftentimes, the best way to do that is to get personal—tell the reader a little bit about yourself. (For more information about ethos, see “ Ethos .”)For instance, let’s say you are writing an essay arguing that dance is a sport. Using the occasional personal pronoun to let your audience know that you, in fact, are a classically trained dancer—and have the muscles and scars to prove it—goes a long way in establishing your credibility and proving your argument. And this use of first person will not distract or annoy your readers because it is purposeful.

- Clarifying passive constructions : Often, when writers try to avoid using first person in essays, they end up creating confusing, passive sentences . For instance, let’s say I am writing an essay about different word processing technologies, and I want to make the point that I am using Microsoft Word to write this essay. If I tried to avoid first-person pronouns, my sentence might read: “Right now, this essay is being written in Microsoft Word.” While this sentence is not wrong, it is what we call passive—the subject of the sentence is being acted upon because there is no one performing the action. To most people, this sentence sounds better: “Right now, I am writing this essay in Microsoft Word.” Do you see the difference? In this case, using first person makes your writing clearer.

- Stating your position in relation to others: Sometimes, especially in an argumentative essay, it is necessary to state your opinion on the topic . Readers want to know where you stand, and it is sometimes helpful to assert yourself by putting your own opinions into the essay. You can imagine the passive sentences (see above) that might occur if you try to state your argument without using the word “I.” The key here is to use first person sparingly. Use personal pronouns enough to get your point across clearly without inundating your readers with this language.

Now, the above list is certainly not exhaustive. The best thing to do is to use your good judgment, and you can always check with your instructor if you are unsure of his or her perspective on the issue. Ultimately, if you feel that using first person has a purpose or will have a strategic effect on your audience, then it is probably fine to use first-person pronouns. Just be sure not to overuse this language, at the risk of sounding narcissistic, self-centered, or unaware of others’ opinions on a topic.

Recommended Readings:

- A Synthesis of Professor Perspectives on Using First and Third Person in Academic Writing

- Finding the Bunny: How to Make a Personal Connection to Your Writing

- First-Person Point of View

Brevity – Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence – How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow – How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity – Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style – The DNA of Powerful Writing

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority & Credibility – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Research, Speech & Writing

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

Can You Use First-Person Pronouns (I/we) in a Research Paper?

Research writers frequently wonder whether the first person can be used in academic and scientific writing. In truth, for generations, we’ve been discouraged from using “I” and “we” in academic writing simply due to old habits. That’s right—there’s no reason why you can’t use these words! In fact, the academic community used first-person pronouns until the 1920s, when the third person and passive-voice constructions (that is, “boring” writing) were adopted–prominently expressed, for example, in Strunk and White’s classic writing manual “Elements of Style” first published in 1918, that advised writers to place themselves “in the background” and not draw attention to themselves.

In recent decades, however, changing attitudes about the first person in academic writing has led to a paradigm shift, and we have, however, we’ve shifted back to producing active and engaging prose that incorporates the first person.

Can You Use “I” in a Research Paper?

However, “I” and “we” still have some generally accepted pronoun rules writers should follow. For example, the first person is more likely used in the abstract , Introduction section , Discussion section , and Conclusion section of an academic paper while the third person and passive constructions are found in the Methods section and Results section .

In this article, we discuss when you should avoid personal pronouns and when they may enhance your writing.

It’s Okay to Use First-Person Pronouns to:

- clarify meaning by eliminating passive voice constructions;

- establish authority and credibility (e.g., assert ethos, the Aristotelian rhetorical term referring to the personal character);

- express interest in a subject matter (typically found in rapid correspondence);

- establish personal connections with readers, particularly regarding anecdotal or hypothetical situations (common in philosophy, religion, and similar fields, particularly to explore how certain concepts might impact personal life. Additionally, artistic disciplines may also encourage personal perspectives more than other subjects);

- to emphasize or distinguish your perspective while discussing existing literature; and

- to create a conversational tone (rare in academic writing).

The First Person Should Be Avoided When:

- doing so would remove objectivity and give the impression that results or observations are unique to your perspective;

- you wish to maintain an objective tone that would suggest your study minimized biases as best as possible; and

- expressing your thoughts generally (phrases like “I think” are unnecessary because any statement that isn’t cited should be yours).

Usage Examples

The following examples compare the impact of using and avoiding first-person pronouns.

Example 1 (First Person Preferred):

To understand the effects of global warming on coastal regions, changes in sea levels, storm surge occurrences and precipitation amounts were examined .

[Note: When a long phrase acts as the subject of a passive-voice construction, the sentence becomes difficult to digest. Additionally, since the author(s) conducted the research, it would be clearer to specifically mention them when discussing the focus of a project.]

We examined changes in sea levels, storm surge occurrences, and precipitation amounts to understand how global warming impacts coastal regions.

[Note: When describing the focus of a research project, authors often replace “we” with phrases such as “this study” or “this paper.” “We,” however, is acceptable in this context, including for scientific disciplines. In fact, papers published the vast majority of scientific journals these days use “we” to establish an active voice. Be careful when using “this study” or “this paper” with verbs that clearly couldn’t have performed the action. For example, “we attempt to demonstrate” works, but “the study attempts to demonstrate” does not; the study is not a person.]

Example 2 (First Person Discouraged):

From the various data points we have received , we observed that higher frequencies of runoffs from heavy rainfall have occurred in coastal regions where temperatures have increased by at least 0.9°C.

[Note: Introducing personal pronouns when discussing results raises questions regarding the reproducibility of a study. However, mathematics fields generally tolerate phrases such as “in X example, we see…”]

Coastal regions with temperature increases averaging more than 0.9°C experienced higher frequencies of runoffs from heavy rainfall.

[Note: We removed the passive voice and maintained objectivity and assertiveness by specifically identifying the cause-and-effect elements as the actor and recipient of the main action verb. Additionally, in this version, the results appear independent of any person’s perspective.]

Example 3 (First Person Preferred):

In contrast to the study by Jones et al. (2001), which suggests that milk consumption is safe for adults, the Miller study (2005) revealed the potential hazards of ingesting milk. The authors confirm this latter finding.

[Note: “Authors” in the last sentence above is unclear. Does the term refer to Jones et al., Miller, or the authors of the current paper?]

In contrast to the study by Jones et al. (2001), which suggests that milk consumption is safe for adults, the Miller study (2005) revealed the potential hazards of ingesting milk. We confirm this latter finding.

[Note: By using “we,” this sentence clarifies the actor and emphasizes the significance of the recent findings reported in this paper. Indeed, “I” and “we” are acceptable in most scientific fields to compare an author’s works with other researchers’ publications. The APA encourages using personal pronouns for this context. The social sciences broaden this scope to allow discussion of personal perspectives, irrespective of comparisons to other literature.]

Other Tips about Using Personal Pronouns

- Avoid starting a sentence with personal pronouns. The beginning of a sentence is a noticeable position that draws readers’ attention. Thus, using personal pronouns as the first one or two words of a sentence will draw unnecessary attention to them (unless, of course, that was your intent).

- Be careful how you define “we.” It should only refer to the authors and never the audience unless your intention is to write a conversational piece rather than a scholarly document! After all, the readers were not involved in analyzing or formulating the conclusions presented in your paper (although, we note that the point of your paper is to persuade readers to reach the same conclusions you did). While this is not a hard-and-fast rule, if you do want to use “we” to refer to a larger class of people, clearly define the term “we” in the sentence. For example, “As researchers, we frequently question…”

- First-person writing is becoming more acceptable under Modern English usage standards; however, the second-person pronoun “you” is still generally unacceptable because it is too casual for academic writing.

- Take all of the above notes with a grain of salt. That is, double-check your institution or target journal’s author guidelines . Some organizations may prohibit the use of personal pronouns.

- As an extra tip, before submission, you should always read through the most recent issues of a journal to get a better sense of the editors’ preferred writing styles and conventions.

Wordvice Resources

For more general advice on how to use active and passive voice in research papers, on how to paraphrase , or for a list of useful phrases for academic writing , head over to the Wordvice Academic Resources pages . And for more professional proofreading services , visit our Academic Editing and P aper Editing Services pages.

Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Scholarly Voice: Writing in the First Person

First-person point of view.

Since 2007, Walden academic leadership has endorsed the APA manual guidance on appropriate use of the first-person singular pronoun "I," allowing the use of this pronoun in all Walden academic writing except doctoral capstone abstracts, which should not contain a first-person pronoun.

In addition to the pointers below, the APA manual provides information on the appropriate use of first person in scholarly writing (see APA 7, Section 4.16).

APA Style and First-Person Pronouns

APA prefers that writers use the first person for clarity and self-reference.

To promote clear communication, writers should use the first person, rather than passive voice or the third person, to indicate the action the writer is taking.

- This passive voice is unclear as it does not indicate who collected these data.

- This third-person voice is not preferred in APA style and is not specific about who "the researcher" is or which researcher collected these data.

- This sentence clearly indicates who collected these data. Active voice, first-person sentence construction is clear and precise.

Avoid Overusing First-Person Pronouns

However, using a lot of "I" statements is repetitious and may distract readers. Remember, avoiding repetitious phrasing is also recommended in the APA manual.

- Example of repetitive use of "I": In this study, I administered a survey. I created a convenience sample of 68 teachers. I invited them to participate in the survey by emailing them an invitation. I obtained email addresses from the principal of the school…

- We suggest that students use "I" in the first sentence of the paragraph. Then, if it is clear to the reader that the student (writer) is the actor in the remaining sentences, use the active and passive voices appropriately to achieve precision and clarity.

Avoid Second-Person Pronouns

In addition, avoid the second person ("you").

- Example using the second person: As a leader, you have to decide what kind of leadership approach you want to use with your employees.

- It is important for writers to clearly indicate who or what they mean (again back to precision and clarity). Writers need to opt for specificity instead of the second person. Remember, the capstone is not a speech; the writer is not talking to anyone.

Restrict Use of Plural First-Person Pronouns

Also, for clarity, restrict the use of "we" and "our." These should only be used when writers are referring to themselves and other, specific individuals, not in the general sense.

- Example of plural first-person pronoun: We must change society to reflect the needs of current-day children and parents.

- Here, it is important to clarify who "we" means as the writer is not referring to specific individuals. Being specific about the who is important to clarity and precision.

Avoid Unsupported Opinion Statements

When using the first-person "I," avoid opinion statements.

As writers write, revise, and self-edit, they should pay specific attention to opinion statements. The following phrases have no place in scholarly writing:

- I think…

- I believe…

- I feel…

Writers and scholars need to base arguments, conclusions, and claims on evidence. When encountering "I" statements like this, do the following:

- Consider whether this really an opinion or whether this can be supported by evidence (citations).

- If there is evidence, remove the “I think…”, “I believe…”, “I feel…” phrasing and write a declarative statement, including the citation.

- If there is no evidence to cite, consider whether the claim or argument can be made. Remember that scholarly writing is not based on opinion, so if writers cannot support a claim with citations to scholarly literature or other credible sources, they need to reconsider whether they can make that claim.

- Previous Page: Anthropomorphism

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Certification, Licensure and Compliance

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

How to Write a Case Study

This guide explains how to write a descriptive case study. A descriptive case study describes how an organization handled a specific issue. Case studies can vary in length and the amount of details provided. They can be fictional or based on true events.

Why should you write one? Case studies can help others (e.g., students, other organizations, employees) learn about

- new concepts,

- best practices, and

- situations they might face.

Writing a case study also allows you to critically examine your organizational practices.

The following pages provide examples of different types of case study formats. As you read them, think about what stands out to you. Which format best matches your needs? You can make similar stylistic choices when you write your own case study.

ACF Case Studies of Community Economic Development This page contains links to nine case studies that describe how different organizations performed economic development activities in their communities.

ATSDR Environmental Health and Medicine This page contains links to approximately 20 classroom-style case studies focused on exposures to environmental hazards.

What are your goals ? What should your intended readers understand or learn after reading your case? Pick 1–5 realistic goals. The more goals you include, the more complex your case study might need to be.

Who is your audience? You need to write with them in mind.

What kind of background knowledge do they have? Very little, moderate, or a lot of knowledge. Be sure to explain special terms and jargon so that readers with little to moderate knowledge can understand and enjoy your case study.

What format do you need to use? Will your case study be published in a journal, online, or printed as part of a handout? Think about how word minimums or maximums will shape what you can talk about and how you talk about it. For example, you may be allowed fewer words for a case study written for a print textbook than for a webpage.

What narrative perspective will you use? A first-person perspective uses words such as “I” and” “we” to tell a story. A third-person perspective uses pronouns and names such as “they” or “CDC”. Be consistent throughout your case study.

Depending on your writing style, you might prefer to write everything that comes to your mind first, then organize and edit it later. Some of you might prefer to use headings or be more structured and methodical in your approach. Any writing style is fine, just be sure to write! Later, after you have included all the necessary information, you can go back and find more appropriate words, ensure your writing is clear, and edit your punctuation and grammar.

- Use clear writing principles, sometimes called plain language. More information can be found in the CDC’s Guide to Clear Writing [PDF – 5 MB] or on the Federal Plain Language website .

- Use active voice instead of passive voice. If you are unfamiliar with active voice, review resources such as NCEH/ATSDR’s Training on Active Voice , The National Archive’s Active Voice Tips , and USCIS’ Video on Active Voice .

- Word choice is important. If you use jargon or special terminology, define it for readers.

- CDC has developed many resources to help writers choose better words. These include the NCEH/ATSDR Environmental Health Thesaurus , CDC’s National Center for Health Marketing Plain Language Thesaurus for Health Communicators [PDF – 565 KB] , CDC’s Everyday Words for Public Health Communication [PDF – 282 KB] , and the NCEH/ATSDR’s Clear Writing Hub .

After writing a draft, the case study writer or team should have 2–3 people, unfamiliar with the draft, read it over. These people should highlight any words or sentences they find confusing. They can also write down one or two questions that they still have after reading the draft. The case study writer or team can use those notes make edits.

- Review your goals for the case study. Have you met each goal? Make any necessary edits.

- Check your sentence length. If your sentence has more than 20 words, it might be too long. Limit each sentence to one main idea.

- Use common words and phrases. Review a list of commonly misused words and phrases.

- Be sure you have been consistent with your verb tenses throughout.

Finally, the writer/team should have someone with a good eye for detail review the case study for grammar and formatting issues. You can review the CDC Style Guide [PDF – 1.36 MB] for clarification on the use of punctuation, spelling, tables, etc.

Green BN, Johnson CD. How to write a case report for publication. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine. 2006;5(2):72-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60137-2

Scholz RW, Tietje O. Types of case studies. In: Embedded Case Study Methods . Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2002. P. 9-14. doi:10.4135/9781412984027

Warner C. How to Write a Case Study [online]. 2009. Available from URL: https://www.asec.purdue.edu/lct/HBCU/documents/HOWTOWRITEACASESTUDY.pdf [PDF – 14.5 KB]

Title: Organization: Author(s):

Goals: After reading this case study, readers should

Introduction Who is your organization? What is your expertise? Provide your audience with some background information, such as your expertise. This provides context to help them understand your decisions. (How much should you write? A few sentences to 1 paragraph)

What problem did you address? Who identified the problem? Provide some background on who noticed the problem and how it was reported. Were multiple organizations or people involved in identifying and addressing the problem? This will help the reader understand how and why decisions were made. (1 paragraph)

Case Details Provide more information about the community. What factors affected your decisions? Describe the community. The context, or setting, is very important to readers. What are some of the unique characteristics that affected your decisions? (1 paragraph)

How did you address the problem? Start at the beginning. Summarize what happened, in chronological order. If you know which section of the publication your case study is likely to be put in, you can specify how your actions addressed one or more of the main points of the publication/lesson.

What challenge(s) did you encounter? Address them now if you have not already.

What was the outcome? What were your notable achievements? Explain how your actions or the outcomes satisfy your learning goals for the reader. Be clear about the main point. For example, if you wanted readers to understand how your organization dealt with a major organizational change, include a few sentences that reiterate how you encountered and dealt with the organizational change. (A few sentences to 1 paragraph)

Conclusion Summarize lessons learned. Reiterate your main point(s) for the reader by explaining how your actions, or the outcomes, meet your goals for the reader.

5 Common Mistakes When Writing A Case Study And How To Avoid Them

by Aaron Larson | Nov 18, 2015 | Marketing , Weekly Articles | 0 comments

Case studies are a powerful marketing tool, and even better piece of content that can positively impact your businesses sales.

Case studies are excellent at creating trust and credibility with customers and prospects, as well as excellent ways for your sales team to better target your audience.

Case studies are great for PR, too.

In reality, however, most case studies fail. They fail because they are either mind numbingly boring, or devoid of any quantitative information that aids buyers in understanding your company’s benefits.

For your pleasure, we’re counting the five most common case study mistakes companies make, how to avoid them, and most importantly how to write compelling, yet persuasive copy in order to publish case studies that your prospects will love.

1) You don’t tell a story (or don’t tell a good story)

Storytelling is the defining difference between other marketing tools such as testimonials. Testimonials talk about how great your company is, rather than making the focus on what you can do for another business. Case studies should be written in third person adding a credibility that first person can’t replicate. By shifting the role of protagonist onto someone else, you gain trust from your audience.

Your company should model the classic story telling arch.

- Conflict/Challenge : Set the scene by introducing the “hero” or company you’re using. Establish their business briefly and what obstacle they were facing. A story has no tension or sakes if there are no obstacles to overcome.

- Climax/Solution: The climax is usually the highest moment of tension in a story. It’s when the humans in The Two Towers are making a final stand against Sauron’s army, when the Rebels are making their life or death strike on the Death Star in Star Wars IV. It’s the moment in the case study when the business has made the choice to switch to your business. Explain why they made the choice, let them know from the previous conflict what was on the line for their business.

- Resolution/Results: Describe what your solution did for the company, what they were able to achieve after implementing your help. Did they save money? Have better organization? Whatever the result, make sure to showcase it.

When a potential client reads your case study, they should be able to insert themselves into the hero’s shoes and image what results you can bring them, rather than flaunting your own company’s glory.

2) You provide no details

As listed in the Resolution/Results above, make sure you spell out in detail what your business did for the case study business. Whether it be “They were able to grow their business from the $300 a week they saved after using…” or, “They had more time to train their walrus army due to the time saved by using…”

Use graphs, pie charts, or any visual images that will highlight benefits.

Providing details like these will help potential clients visualize measurable results for their own business to replicate.

3) You aren’t addressing your audience

It is important when writing a case study to select just one audience to speak to. If you cater to multiple types of clients; tailor each case study to address one persona.

When writing, focus only on the details that this persona would care about, and address their needs and concerns.

4) You don’t have focus

Many times case study writers want to talk about all the aspects they’re working at fixing, but without focus you will confuse your readers and you’ll come across salesy.

Much like focusing on one persona, choose an angle that will highlight your company the best. Even if your company solved five problems for that business, pick the two strongest (or one) and emphasis that aspect.

Possible angles you might choose include:

- Customer Service

5) You don’t have customer quotes

You can tell the most epic story in your case study, but if it doesn’t have a quote from your client the case study will lack a sense of humanity. It’s also vital that you interview real customers, do not lie or make them up, even if your customer is going to approve them.

Quotes generated by a marketing team will sound flat and artificial compared to what your customer will say in his or her own words. Get your case study quotes in your customers own words, as this is the most impactful for those reading it.

Not sure how to develop an effective case study?

If you want to see how your peers have solved their marketing and website problems, take a look at our portfolio , and see what others have said about the result.

And if your IT firm wants to learn more about what steps to take with your own marketing initiatives, or would like a free consultation, contact us here .

By Solution

Project Management

Document Collaboration

Contact Center

Marketing Tools

Low Code App Development

By Department

RingCentral

- Case Studies

Writing Case Studies – a How To Guide

A case study is a descriptive, exploratory or explanatory document that analyzes a person, object, event, situation, or idea. People may find themselves writing case studies in different industries for different purposes. Some examples include:

- Marketing or sales case study to highlight a product or service and its benefits

- Educational or learning case study that highlights a situation and a resolution

- Life or social science case study that explores causation and principles

- Medical case study to record clinical interactions with patients

Marketing and sales case studies are success stories of a product or service used with a customer. The case study explains how the product or service was used and its return on investment. Most marketing and sales case studies have the following three sections:

- Challenge or problem (introduction and description of the business or customer’s problem)

- Solution (how was the solution selected and implemented)

- Results and benefits (benefits and return on investment for the customer, use data)

Determine the Goal

One of the first steps in creating a case study is determining the purpose and goal. The following questions can help you determine the goals you want to accomplish:

- Who is the audience?

- What product or service are you featuring?

- What is it that you want the reader to know?

- What do you want the reader to learn or do after reading this document?

Capture the Information

A marketing and sales case study is usually a story of success. Once you determine the purpose, you will decide the topic or subject area you want to highlight. Be sure to stick to one topic, as addressing multiple topics in one case study can be confusing. For the chosen topic, you will need the following information:

- Rationale for the case study and information about the customer

- Background information, data and description about the challenge or problem experienced by the customer. Any data, stats, or numbers that relate to the problem.

- The service or product you used to solve the problem. This can include why it was chosen, the process and methodology used for implementation.

- Details and data about the results and benefits. Data with measurable results is essential for this section.

Next, you will need to determine if you have all the information. In many cases, you may have to interview the customer and/or others to get all the pertinent information and data to support the case study. When interviewing others, make sure you are prepared with a list of specific questions to ask the customer and others. You want to be sure that you are getting the specific data you need to write the case.

Depending on the case study, in general it can vary from 1 – 3 pages long with 1 – 3 paragraphs for each section. Often, each page has a graphic or picture for visual interest. The font and colors should be easy for printing the case study. A white background with a standard font is best, especially if potential customers and others are downloading the case study.

Writing Case Studies for Educational or Learning purposes often involves a type of problem-based teaching where a situation or challenge is presented along with a resolution or various resolution options. The document will include information about the situation, background information, challenges highlighted, data presented, and solutions evaluated. Sections may include:

- Project or situation summary

- Challenges/Key Issues

- Team/Individual Activity

Determine the Learning Goal

One of the first steps in writing this type of case study is determining the objective or learning goals. The following questions can help you determine the learning goals:

- What do you want the reader to know or do after reading this document?

- Do you want the reader to learn about multiple aspects of a problem or solution or just a single solution?

- Do you want to present all of the data or do you want the learner to determine what additional data or information is needed?

- How will the case study be presented? Will it be part of a learning classroom with group discussion and team exercises? Will it be part of a team meeting and discussion? Will it be a stand-alone document that an individual can read without an instructor?

The information for the case study can be ascertained from your own professional experience, from current or historical events, from books or other resources. In writing an educational or learning case study, you will need the following:

- A structured and engaging story that tells an interesting situation or challenge.

- Understanding of the key issues or challenges. In many cases there are no clear solutions or may have more than one solution.

- Data and background information about the people, location, situation, actions, etc.

- A scenario that provokes questions and encourages the reader to analyze the situation and solutions.

- Information about the key decision makers and stakeholders in the case and their roles and perspective.

Determine if you have all the necessary information or if you will need to conduct research or interviews. When interviewing others, make sure you are prepared with a list of specific questions to be sure you are getting the specific data you need to write the case.

The case study can vary in depth from one to 20 pages or more. The font and colors should be easy for printing the case study. A white background with a standard font is best, especially if the case study is downloaded and printed numerous times.

Project or Situation Summary

Consultant met with a client who was struggling to determine the proper path to move their business due to some key factors and issues. The Client Company is 17 years old with 51 employees, 10 of which are sales, 24 are in operations, and the rest in administration. The company has been struggling to determine the best method to manage all aspects of its human resource, accounting, operations, and sales systems.

The Client Company worked with an IT firm over a 2-year period with little success in integrating all key solutions.

Challenges and Key Issues

- Already invested nearly $100k into current infrastructure

- Losing productivity because systems are not well integrated

- Poor internal selection processes of solutions

- Staff is not trained on the current applications and their cross functionality

- Accounting and Operations applications are not communicating which leaves staff double entering data

- Cross-over of duplicated functionality in various systems which makes determination of where to enter data challenging

Consultant met with his key team members to determine which solutions were most reliable to create integration of software solutions, reduction in IT overhead, improvement in system processing and better training for The Client Company personnel.

The solution offered by Consultant cost $150k, plus the total cost of year-over-year ownership of $35k in recurring software licensing fees. The solution could be implemented within 6-months from a signed statement of work.

In addition, the Consultant offered a phased implementation approach to help reduce the initial financial start-up burden.

The solution virtually reduces the client’s software applications from 7 internal and external facing applications to 5. Of the five applications, four exist in the infrastructure and one is a new application to eliminate the gaps in the Accounting and Operations department.

The new application is expected to reduce wasted employee hours by 25% through the elimination of double entry, improved synchronicity, and better notifications when tasks are complete. This reduction in wasted time equals nearly workforce cost savings of $200k per year.

Client Company decided to stay with the existing infrastructure because they had invested so much money over a two-year period that they felt an additional $150k outlay of capital was cost prohibitive. While there was a real ROI for the Accounting and Operations system, they felt it was important to preserve existing jobs and would consider a more reliable solution in 18-months.

Team Discussion

- What additional challenges should have been uncovered during the business analysis phase?

- Determine which challenges were the most significant impact to their current pain points?

- Discuss how those challenges could have been used to sell the consultant’s solution with more persuasion.

- What other solution could you have offered that may have been successful in off-setting more of the cost?

- What different approach may have been taken to create a different outcome (e.g. working with their existing applications and improving process?)

- Grab the reader’s attention with a catchy and descriptive title

- Write the case study in first person (“I”) or third person (“he/she”).

- Make the case study easy to read and scan. Use bulleted lists, short paragraphs, and highlight your point.

- Consider the reader’s point of view and what information is important to them.

- Write out acronyms and consider your audience when using industry-specific terms and jargon.

- Always include the author or your business contact information.

- If you gathered data or information from others in helping you write the case study, send them a copy to review. They should be checking to make sure the information is correct.

- Use professional-looking photographs, graphics, layouts, etc.

- Have someone proofread and edit the case study.

- Decide how you will use and share the case study once it is complete.

When writing case studies, they should be customized to your needs. It could include additional sections such as background or evaluation sections. It can contain graphics and pictures related to the specific topic. It should also reflect your company’s branding.

If you have additional questions or need support, contact us at:

Positive Results™ Custom Business Solutions

- 440.499.4944

https://PositiveResults.com

We're here to help.

Learn more about how technology can help you work smarter..

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- 30628 Detroit Rd., Suite 142 Westlake, OH

Social Media

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Additional menu

Damien Elsing Copywriter

Copywriting & Marketing Consulting

How to Write a Case Study (with Bonus Template)

March 27, 2014 By Damien

This article was originally published in 2014 – last updated August 2020.

A lot of people over-think case studies and panic at the mere mention of them.

I know this because as a freelance copywriter I’m forever gently nudging clients to collect case studies – a process that’s a lot like pulling teeth sometimes!

But a case study doesn’t need to be long — it just needs to explain the result that your product or service achieved for your customer. It can be as short as a paragraph or two, provided it checks all the boxes we’ll look at below. In fact, the shorter it is, the more people will read it. Who wants to sit down and read a 1000-word document about how great your business is?

I’m going to explain how to write a great case study quickly, and I’ll also include a simple template for gathering case studies you can simply fill in the blanks and present to your customers.

But first…

What are case studies and why should you use them?

A case study is like a testimonial on steroids. It takes random client feedback that everyone uses as “testimonials” and puts it into a real world, relevant context in the form of a story.

They work because they allow customers to see first hand how your product or service specifically helped others in the same situation as they now find themselves.

The format for a case study should be a story. It should follow a structure of beginning, middle, and end.

The “beginning” is the challenge facing your customer. The “middle” is the way you approached solving this problem or challenge. The “end” is the result experienced by the customer.

Where to use case studies

There are a few points to keep in mind when using case studies:

Terminology – Firstly, don’t call a case study a “case study”. Call it a “success story”. “Case study” sounds boring. Success story, on the other hand, promises not only a story, but a story about somebody’s success! We all love stories, and we all love success – especially when it’s success we too could be experiencing really soon (do you see where this is going?).

Placement – You should make your existing case studies as prominent as possible when making initial contact with prospects. This includes on important pages of your website and in sales and marketing collateral such as a price list or brochure. There’s also a place for creating separate case studies for lead generation – you can position these like a “How to” – showing the way you solved the client’s problem. In general though, case studies are best used when integrated with other material as supporting information rather than used in isolation.

Relevance – Ideally you’ll have more than one case study, and then you can figure out the best place to use them. For example, if you offer three distinct services, include a success story about a particular service on the relevant service page of your website (or when in sales conversations with that persona). Try not to lump them all in together (although there’s nothing wrong with also having a section on your website called “success stories” that repeats the information).

How to gather the raw information for the case study

There are three ways you can get the information you need to write a case study:

1. Phone – Calling your customer for a chat is going to yield great results. Make sure you use hands free so you can type notes, or better yet record the call so you can go over it later at your leisure. The great thing about a phone (or face to face) chat is that you can prompt them to go into more detail about certain points. Also, people are naturally more effusive verbally than they are when writing. Of course, explain you’re going to be using this information in a case study and make sure they’re okay with that before you start asking questions. Also reassure them they will get final say and you won’t put words in their mouth – this will make them more relaxed about what they say.

2. Email/Survey – This is not as good as using the phone, but if you can’t call your customers or have a lot of customers and simply want to ask them all for case studies (call it “feedback” though) then text/email will have to do. Use the questions outlined below, and when you’ve got the answers back, choose the ones you’ll be using and follow up to say thank you, we loved the feedback so much we’d like to use the information in an individual case study.

3. Video (advanced tactic) – this is where you film the customer answering the questions. Yep, this is the granddaddy of customer success stories. You’ll basically be making a mini documentary about your customer and how you helped them. Nothing beats that face to face connection of seeing and hearing the person talk about how you helped them achieve their desired outcome. If they are willing, you can do this via a Zoom call, or they can just record some video on their phone running through the questions below.

You can then upload this video to Youtube (with the customer’s permission of course) and use it on your website, in the footer of emails, in pitches/presentations, online PDFs, and anywhere else you can think of. If you have the budget then hire a videographer to make this as professional as possible, or just record it on your phone or tablet, which is still far better than no video at all.

Questions to ask

This isn’t set in stone, but this is the loose flow of questions you want to take your customer through:

- What challenge were you facing when you went looking for [name of solution]?

- What made you choose [business name] to overcome this challenge?

- What concerns (if any) did you have about using a [general product/service name]?

- What was it like using [specific product/service name]? Describe the process.

- What was the outcome of using [specific product/business name]?

- What would you say to other people considering using [specific business/product name]?

(Click here to download these questions as a case study template in a Google doc (no opt-in required))

You might not want to use all these questions if they don’t quite fit. It’ll depend on the nature of your product or service, but you want to be asking at least four of the above six questions, and 1, 2, 4, and 5 are crucial for getting the whole picture.

Writing your case study

Once you’ve got the answers to the above questions, you want to put it all together in a narrative. It’s not going to work as well if you use a Q&A format because it takes away from the flow of the story, so this is where some creativity is required in putting it all together. You can use some creative license here, provided you capture the spirit of what the person was trying to say and don’t twist their intention. Remember, you’ll be getting their permission before publishing this so don’t worry too much about writing what they say word for word.

Another thing to consider is whether you want to make it first or third person. For example, first person would be from the customer’s perspective (“I found they were really easy to work with…”) and third person would be “Judy loved how easy ABC Widgets were to work with…”. I think first person is always stronger because it sounds like the praise is coming from the customer, not you. You might use third person for a more detailed case study and just include elements of the first person story.

Let’s look at a real world example for a client I worked with…

Here’s the raw data that the customer sent back to my client, a property investment and buyer’s advocacy firm, via email:

1) What make you seek out a Buyer’s / Vendor’s Advocate. What problem were you having? To get an advantage over other buyers in the market. I engaged [business] due to their unique group block buying strategy. The strategy is market leading in my view as I was able to purchase an apartment below market value, in a blue chip location, and with the attraction of adding immediate value from renovations. The issues I was experiencing prior to engaging [business] was competing against too many emotional buyers who were constantly driving up prices, particularly at auction. Using the services of [business] gave me an advantage over my competition. 2) What were your concerns about using a Buyers / Vendor’s Advocate to solve these problems? Whether the apartment purchased would be renovated in a timely manner. My other concern was whether my apartment would be tenanted quickly given that other investors would be renting out their apartment (within the same block) at the same time. As usually these type of purchases attract investors. 3) Why did you choose Advantage? For the reasons outlined above. Plus [business owner’s] reputation in the market. [business owner] has the runs on the board which makes my decision easy every time. 4) What did you enjoy about working together? One word, they got the results over and over again. I have now purchased 3 properties via the group block strategy and each time they have outperformed the market. 5) What results did you get from the service? Outstanding. This also includes the property management service [business] provide. The guys who manage my properties are sharp, proactive and treat my investments as if it was their own.

And here’s how we can weave this into a success story:

“They outperform the market every time…” “As an experienced investor, I was looking for a way to get an advantage over the market. I found I was constantly competing against emotional buyers who were driving up prices. I needed to find an edge over the competition. I chose [business name] because of their reputation. They have the runs on the board, which made the decision easy. My only concerns were whether the apartment we purchased would be renovated fast, and whether we’d be able to rent it out, given that there were several other investors in the same block. But not only did [business name] get a great return for me, they even managed the property for me! And the guys who manage the property are sharp, proactive, and treat my investment like it was their own. I’ve now used [business name] three times, and they’ve outperformed the market for me every time.”

See how putting this into a story format makes it much more engaging and easy to read?

You could approach the “story” part in any number of ways, leading with whatever is most important to your customers. But the important thing is that it has a clear structure: problem, solution, result.

Points to keep in mind

Note the headline – you want to take the most impressive (or relevant) quote from your entire case study and use it as the headline to grab attention. Keep your customer in mind. In the above example it’s property investors, so they’ll be most interested in a strong return on their investment.

Stick to the structure of the questions – use the original questions to guide you. The customer will often answer the questions out of order and add irrelevant information, so it’s up to you to do some fancy editing and just keep the good stuff, sticking to the original flow of questions as you go.

Include the customer’s concerns – you might be wondering “why add the negative concerns the person had?” It might seem counter-intuitive to do this, but it’s important to keep them in. Here’s why: it’s likely the reader has the exact same concerns , so acknowledging these objections and addressing them will help overcome them. It’s important to address your customer’s objections in any type of sales or marketing, not just ignore them and hope the’ll go away.

Come back with fresh eyes – as with any sort of writing or editing, it’s important that you come back to your case study a day or two later and just make sure it all makes sense and you haven’t left anything out. Better yet, show it to a friend or colleague for their feedback and ask them for any suggestions to make the story more compelling.

Add a photo and the person’s full name – You need to make the case study as real as possible. Anonymous success stories aren’t going to cut it, and neither will a last initial such as “John B.”. These look made up. So you need to at least add the person’s full name (and their company name/position if it’s B2B – suburb or city if it’s B2C). It can be weird asking, but also try to get a photo of the person to use with the case study. The worst that can happen is that they say no and you’ll be no worse off than you are now!

The bottom line on gathering and writing case studies

Case studies are a valuable and relatively cheap and easy way to convince customers that your product or service will work for them. These type of success stories should be part of your overall business story, and should be used strategically so that they’re relevant to the customer and used at the right stage of the buying cycle.

Share your own case study tips and experiences in the comments section below!

Reader Interactions

March 31, 2014 at 8:02 am

Great article! I really appreciate your idea to call the case study a “success story”. It really helps frame the piece. Afterall, that’s what it is! Also, many companies use e-mail surveys regularly (possibly with an incentive at the end) to get honest feedback from clients. I think that could still be a good alternative to making phone calls, where the customer may feel like they’re being put on the spot. The survey would allow you to get exact quotes for the case study content, and maybe even find some areas for improvement, too. Thanks for all of these ideas — and for posting the template! I’m definitely going to be using this.

March 31, 2014 at 10:35 am

Good points, Annie. The phone call option is really for people who have a fairly personal relationship with the clients, such as a service business or consultancy.

Yeah surveys would be great for any kind of business where you don’t have a one-to-one relationship with the customer. Also a great way to gather constructive criticism, killing two birds with one stone.

Thanks for your feedback!

March 31, 2014 at 7:02 am

April 2, 2014 at 1:45 pm

I never wrote a case study but I have seen a lot of them through my day job. They are usually pretty interesting reads. Always wondered if I need to have case studies for my illustration business but wasn’t sure.

April 2, 2014 at 2:08 pm

Hey BD, I think they can be really useful for any business in an industry where people are making decisions about hiring you or buying your product. Give it a go!

January 2, 2016 at 5:44 pm

Enjoyable article but template cannot be found and image of answers to case study questions missing.

August 3, 2020 at 1:36 pm

All fixed now, sorry about that Lsai.

Get Started

Get the edge on your competitors with compelling copywriting, done for you.

Let’s Talk

Looking from within: Comparing first-person approaches to studying experience

- Open access

- Published: 30 September 2021

- Volume 42 , pages 10437–10453, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Anna-Lena Lumma ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5631-8988 1 &

- Ulrich Weger 1

8162 Accesses

17 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Fostering our understanding of how humans behave, feel and think is a fundamental goal of psychological research. Widely used methods in psychological research are self-report and behavioral measures which require an experimenter to collect data from another person. By comparison, first-person measures that assess more subtle facets of subjective experiences, are less widely used. Without integrating such more subtle first-person measures, however, fundamental aspects of psychological phenomena remain inaccessible to psychological theorizing. To explore the value and potential contribution of first-person methods, the current article aims to provide an overview over already established first-person methods and compare them on relevant dimensions. Based on these results, researchers can select suitable first-person methods to study different facets of subjective experiences. Overall, the investigation of psychological phenomena from a first-person perspective can complement and enrich existing research from a third-person perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

The overlooked ubiquity of first-person experience in the cognitive sciences

Personal Construct Qualitative Methods

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the study of psychological phenomena, researchers often take the perspective of an outside observer to gather data about their study participants. This so-called third-person perspective can be regarded as the gold-standard approach in mainstream psychological science. Here, we want to emphasize that psychological phenomena contain several layers and that each layer of a psychological phenomenon needs distinct methods with which they can be studied. Some layers are outwardly observable such as talking, responding to a question, body movements, social interactions, facial expressions, eye movements etc.. In addition, psychological phenomena also contain an internal layer which is only accessible to an internal point of view. This internal layer represents the experiential facet of psychological phenomena (e.g. How does a given experiential content arise in my awareness and how does it unfold over time?). Both the external and internal dimensions are implicated in the other to some extent. However, we assume that subtle aspects of an internal experience can possibly not be observed from an external point of view, it must ultimately be inferred or approximated through second-person or third-person measures. Note however, that whether and how a third person can observe experiential states of others, is still debated in the literature on empathy and knowing other minds (Gallagher & Zahavi, 2008 ). According to theory of mind for instance, understanding others is inferred through prior folk psychological knowledge and based on inferential mental operations (Baron-Cohen et al., 1985 ; Carruthers & Smith, 1996 ). In contrast, simulation theory posits that we come to know others by internally simulating others’ feelings, behaviour and beliefs (Gallese & Goldman, 1998 ; Gordon & Cruz, 2003 ). Finally, embodied and enactive approaches suggest that others can be known through direct perception (De Jaegher, 2009 ; Fuchs & De Jaegher, 2009 ; Gallagher, 2008 ). We suggest that a person, who undergoes an experience can be aware of distinct aspects of an experience to different degrees (e.g. a person might not be aware of subtle precursors of an experience of sadness, but notice the sadness once strong bodily sensations are consciously noticeable). If a person, who undergoes a specific experience is fully aware of all aspects and components of that experience (e.g. precursors of an experience of sadness), it can potentially also be expressed in outwardly observable behaviour (e.g. describing fleeting dynamics of thoughts as potential precursors of sadness) and thus also be observed by other people or measures through third-person approaches. However, if a person is only partially aware of the nuances of an experience, it might not easily be possible to infer these aspects of an experience through third-person measures. Therefore, we suggest that more subtle and pre-reflective aspects of a subjective experience (e.g. the unfoldment of an experience) require that a person herself can be aware of this internal dimension of an experience. Some first-person methods and practices including mindfulness can guide people to become aware of more subtle facets of an experience (Lundh, 2020 ). We suggest that a person, who is either trained or guided through respective first-person methods can better grasp more subtle aspects of experiences over time and then translate these new nuances of the experience into verbal descriptions or express it through different types of behaviour.

Overall, internal dimensions of subjective experiences are usually not widely and directly studied. We suggest that the internal dimension also needs to be systematically studied and added to the existing research catalogue in the study of psychological phenomena. The so-called first-person perspective and respective first-person methods offer a fruitful way to study the internal dimension of psychological phenomena.

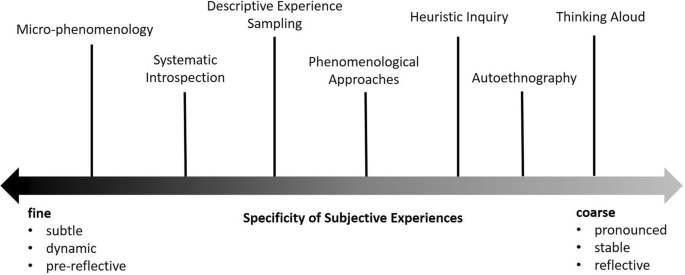

Therefore, the aim of this manuscript is to provide a first exploratory overview of existing first-person methods and contribute to the advancement of the study of psychological phenomena from a first-person perspective. More specifically, this manuscript covers first-person methods, which can capture more subtle, pre-reflective and fine-grained aspects of subjective experiences. This overview of first-person methods describes the core goals of each method and exemplary studies as well as advantages and weaknesses of each method. The first-person approaches covered in this manuscript emphasize different facets of subjective experiences and might have opposing perspectives on how to best study subjective experiences. Furthermore, some of the presented first-person methods can be regarded as work in progress. Thus, rather than providing a finalized strategy about how best to apply first-person methods, this overview aims to initiate a discourse about the applicability and further advancement of different first-person methods.

Generally, first-person methods can be regarded as methods, which provide first-person data about an individual’s subjective experience (Feest, 2014 ). Furthermore, a variety of different first-person approaches can be used to produce first-person data. As pointed out by Schmidt ( 2018 ) phenomenological and introspective approaches could be grouped together because they both “ explain first-personal experience by revealing their structure, relevant tacit aspects and processes, and their experiential unfolding over time. ” (p. 4). More recently Rigato et al. ( 2019 ) suggested in a review of first-person methods that “ first-person experience has always been and is still central to investigations of the mind even if it is not recognized as such .” (p. 1). Therefore, the questions arise how different types of first-person methods elicit first-person data and how particular types of first-person data can be used in different research frameworks. The focus of the manuscript is particularly on first-person methods, which capture more nuances of subjective experiences in contrast to shallow first-person experiences elicited through self-report questionnaires. Furthermore, we suggest that several open research questions (also see in the conclusion and Table 1 ) still need to be addressed to fully agree upon a final definition of a first-person method, because the field is still in its infancy.

Here, we suggest that the internal and experiential dimension of psychological phenomena are predominantly subtle, pre-reflective and dynamic. Therefore, specific methods are required to capture this degree of granularity. Furthermore, we propose that a first-person method provides in-depth and rich data about the experiential dimension of psychological phenomena from an internal perspective. First-person data about the internal perspective should ideally stem from the researcher’s own mind through the application of a systematic self-observation. However, untrained participants could also be guided to perform a systematic self-observation with the help of a trained researcher.

The following example illustrates the benefit of adopting a first-person perspective and considering more subtle nuances in the study of psychological phenomena. Consider a person who suffers from symptoms of severe stress. From a third-person perspective a physician could identify the symptom of stress through measures of the activity of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, stress hormones, muscular tension or behavioral measures. To gain more in-depth insights about emotions and thoughts related to the stress symptoms, open questions could be asked or a more direct interaction could be ensured through an interview with the person.

We suggest that it is possible to go even further and adopt a genuine first-person perspective that captures more fine-grained and subtle nuances of an experiential state – and can hence lend breadth and profundity to the characterization of psychological phenomena. In addition, it allows the affected person to become aware of a (mental health) problem earlier than at a point when symptoms are already noticeable to third-person exploration.

In the above example the person suffering from stress could adopt a first-person perspective and try to observe specific dimensions of his experience during the experience of stress. Novel facets of the experience of stress, which were previously unknown might come to the surface and potentially inspire further research including behavioral or physiological measures. Moreover, additional insights about the experiential dimension of stress could also be relevant for developing more targeted interventions for coping with stress.

Even though first-person approaches are crucial for an integrative understanding of psychological phenomena (Pérez-Álvarez, 2018 ), they are rarely used in mainstream psychological science or recognized as such (Rigato et al., 2019 ). Especially in the past three decades, modern neuroimaging techniques and other physiological methods have greatly influenced the study of psychological themes such as consciousness and the self. It is often assumed that neural correlates of psychological states provide meaningful insights into the workings of the mind (Choudhury et al., 2009 ). However, establishing such relationships is often difficult because questionnaire items usually cover a time frame of minutes, hours, days, and sometimes even weeks and months. Neuronal measures, by contrast, capture brain activity on a time frame of milliseconds or seconds. In order to for instance investigate how the subjective experience of pain is related with neuronal activity, it is important to match the temporal resolution of both measures. If neuronal activity is measured with a temporal resolution of milliseconds, the respective first-person method should also measure the subjective experience of pain with the same temporal resolution. Therefore, first-person methods need to be selected carefully in order to ensure meaningful relationships between subjective experiences and behavioral or physiological data (Bitbol & Petitmengin, 2017 ).

First-person methods were of crucial relevance in the founding period of empirical psychology when experiential states were studied introspectively. In recent years, first-person methods enjoy a renaissance in the scientific study of the mind and several researchers discuss novel ways to study experiential facets of psychological states (Jack & Roepstorff, 2002 ; Overgaard et al., 2008 ; Roth, 2012 ; Varela & Shear, 1999 ).

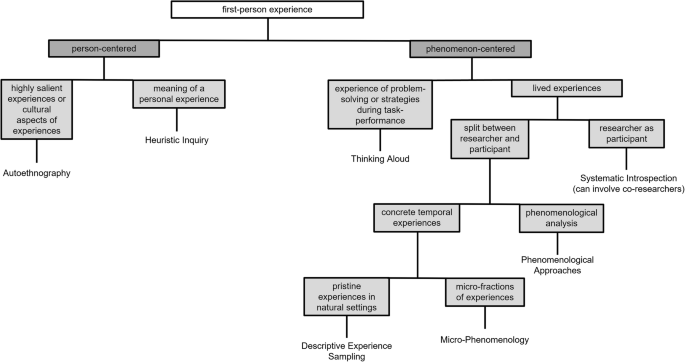

The current overview aims to provide an on overview of already existing first-person methods that are used in the study of experiential aspects of psychological phenomena and that can guide researchers to select a method for their own research. Commonalities and differences of each first-person method is characterized on five different dimensions of interest. These dimensions of interest include 1) a brief description and goal of the method, 2) the relationship between researcher and participant, 3) the type of acquired data, 4) advantages and weaknesses of the method and 5) exemplary studies and fields of application. We would like to emphasize that first-person methods are still in its infancy and that the selected first-person methods are not exhaustive. Moreover, this article aims to contribute to the advancement of a first-person science and enable a greater crosstalk between first-person and third-person research.

Selection Strategy and Dimensions of Comparisons

Selection strategy.

The authors chose to present seven approaches that they considered to be of broader relevance in the qualitative research community. The selection was mainly based on personal assessment and extensive readings and discussions amongst both authors. The final selection of the approaches is an initial attempt to present and compare existing approaches. Note that we did not include any of the classic introspective methods such as those originally used by Titchener (Titchener, 1901 –1905) or the Würzburg School (Hackert & Weger, 2018 ), but rather focused on recently developed methods that are widely in use. And yet, these more recent methods are often based on or are even rooted in the more traditional approaches which hence – in their way – still play a crucial role in the methods discussed here. The five dimensions of interest are briefly explained.

Description of Dimensions of Comparison

Core description and goal.

This dimension provides brief and basic information about respective methods and describes the main goal of the method. Furthermore, this dimension provides basic information about requirements, which need to be met in order to implement the method. Information from this dimension can give a first general overview of the rationale of the particular first-person method of interest. It is not possible to cover an in-depth description of the respective methods within the scope of this manuscript. However, detailed information about the presented methods can be found in the referenced articles.

Researcher-Participant Relationship

This dimension provides information about the relationship between the researcher and participant regarding the respective method. For some methods there might be a clear separation between the role of the researcher and the participant. Standard laboratory methods usually draw clear boundaries between the participant from whom data is recorded on the one hand; and the researcher, who records and analyzes the data on the other. However, there might also be methods which actively engage the participant in the research process and in some cases there might thus be no split between researcher and participant.

Acquired Data

This dimension provides information about the types of data that are acquired with each first-person method. Some methods allow a very open mode of data collection without many prior restrictions and guidelines. Other first-person methods gather data in a systematic manner and provide systematic ways to analyze and structure the data. Furthermore, it could be helpful to know whether data about subjective experiences are concurrently or retrospectively retrieved.

Advantages and Weaknesses

This category provides information about the advantages and possible caveats and weaknesses of the first-person methods.

Exemplary Studies and Fields of Application

This dimension provides information about how the respective first-person method is applied in published studies and.Furthermore, it provides suggestions for potential fields of applications.

In the subsequent sections, each of the selected first-person methods will be described regarding the dimensions of comparison.

Autoethnography

Core description & goal.

Autoethnography can be regarded as a combination of ethnographic and autobiographic research, which investigates personal experiences in a systematic way (Ellis & Bochner, 2000 ). Autoethnographic research can be implemented in many different ways and include the study of personal experiences of other people or the personal interaction between people. It can also place a focus on the personal experience of the researcher herself (Ellis et al., 2011 ). Autoethnography can for instance be implemented by studying the personal experience of members in specific cultural field or it can be applied by the researcher herself to recall or investigate s a specific (often emotional) biographical event or personal experience. An analytical approach of autoethnography adopts more systematic guidelines and particularly emphasizes to gather data of several sources of observation and commit to theoretical analysis of the obtained data (Anderson, 2006 ). In addition, an evocative type of autoethnography makes use of the researcher’s experiences and emotions regarding a personal life event such as birth, loss of a loved one or personal achievements in certain fields (Ellis, 1991 ; Ellis, 1999 ). Furthermore, evocative types of autoethnographic research aim to induce resonance in the readership through describing personal experiences in an emotional comprehensible manner. Overall, autoethnographic research should not merely represent narratives about personal experiences, but also include a systematic analysis of such experiential data and integrate the findings into relevant research frameworks (Ellis et al., 2011 ). Finally, to apply autoethnography, the researcher needs to be personally acquainted with the research topic by either having had a specific experience herself or by immersing herself in a specific cultural field with members who are experts in the field. When focusing on a specific social milieu, respective guidelines for conducting ethnographic research need to be considered. The researcher can also solely focus on personal experiences of other people.

In some cases the researcher only relies on her own experiences (e.g. in the case of evocative autoethnography) – in which case there is no split. She might also focus either exclusively or in addition on the experience of others and conduct additional research, e.g. in field research or with interviews, which create s a split between the researcher and the participant (e.g. in the case of analytic autoethnography).

The acquired data can rely on present observations in one’s own life or field research and on retrospective descriptions of past personal experience of the researcher or his/her participants. Other relevant sources, observations from field research, data acquired from co-researchers and already existing data could also be integrated in the data recording process. Systematically analyzed data can be accompanied by e.g. personal stories, short stories or poetry.